Crisis in Architecture

Passionate constructive criticism from someone who is not an architect, but who loves architecture

Table of Contents

This post is part of the series, Re-imagining architectural practice

Back to the future

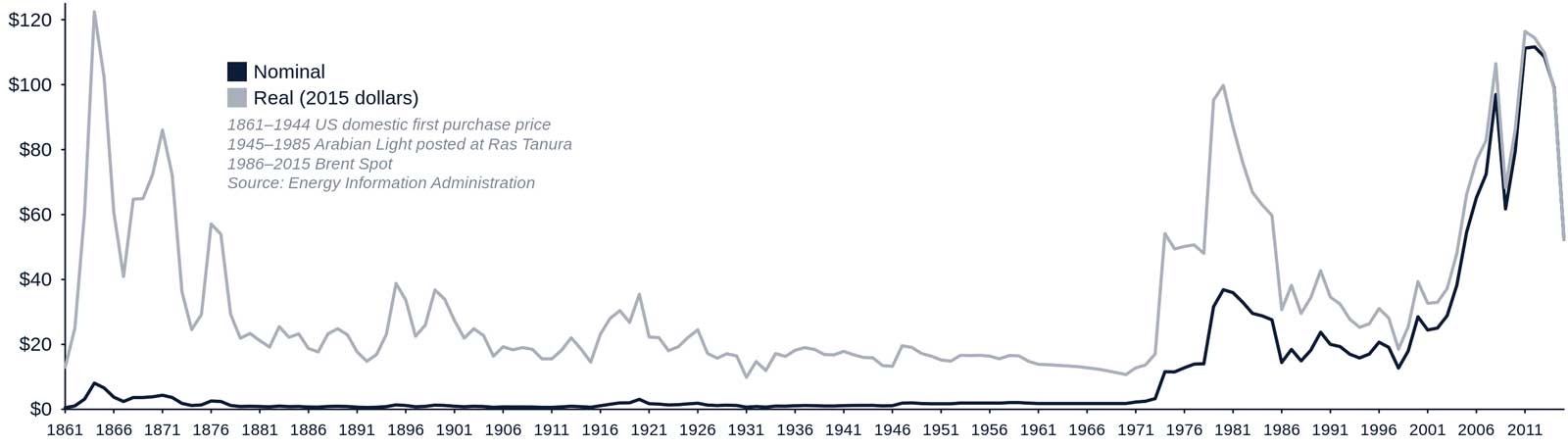

I hold, in my hand, a book in which the author, in his introduction, references an economic crisis (inflation, high energy prices, anaemic growth), demands a reassessment of our consumption-driven use of energy and natural resources, and wasteful redevelopment which includes demolition of buildings which might otherwise have been suitable for adaptive re-use. He questions the concept of growth(ism) itself, advocating for de-growth. He laments the inequalities produced by rampant and rootless land speculation, in which architects have been co-opted and corrupted. Furthermore, he acknowledges the limitations of architects to change the situation on their own, but insists that a fundamental reassessment of the nature of building is necessary: “If Architects are to work for the satisfaction of human needs, very big changes are required in the structure of client demand, and in the financial and other controls applied to building”.

We have not even completed two pages in this book.

The year of publication is 1974.

“If Architects are to work for the satisfaction of human needs, very big changes are required in the structure of client demand, and in the financial and other controls applied to building”

Alienation

McEwan hints at the source of much of the alienation in our cities today, which is the rearrangement, ordained by the demands of capital (property development), of ourselves and our lives in forms of the built environment that do not support constructive human interaction. How many of us, whether living in tower blocks, mansion blocks or terraced houses, do not even know our neighbours, much less provide emotional, social or financial support to them? While the physical context of pre-and post-war slums, say in Glasgow, as identified, were deplorable, and a desire for wholesale renewal shared by residents and authorities alike, the subsequent nature of that renewal broke the social links that had existed in the physically unpalatable circumstances. Given that our current built environment is effectively ‘here to stay’, surely we must now find a way to eliminate the alienation and bring back 21st-century forms of social cohesion.

Form follows finance

Though the title of this book focuses on ‘architecture’, McEwan rightly shines a spotlight on the key underlying interests of the architectural environment – namely land. In framing the city as “a gigantic enterprise, an organisation for the production, distribution, and redistribution of wealth”, he is able to highlight watershed events such as the 1959 Town and Country Planning Act, a precursor, from a developer’s standpoint, to much of what we criticise about ‘free’ market-focused neoliberal thinking. He reminds us that “[t]hose with greater resources command urban space, those who lack resources are, David Harvey's words, trapped in it. Architecture is concerned with physical space, but the allocation, use and design of space are socially controlled by those who command the resources, and deploy them in response to the market."

Again, this is 1974, quite an ‘innocent’ era for ‘free’ markets compared to the post-Thatcher re-engineering of Britain’s financial landscape. Decades later, Alistair Parvin reiterates that "form follows finance", and equally that our housing problem is, in fact, a land problem. These statements ring true, even more so now than when MacEwen made his observations. Perhaps the challenge that we must present ourselves is to divorce the process of development from the necessity of land ownership.

It is frustrating to read that half a century ago, the government was appealing to banks to limit their lending for property development, structurally unproductive compared to industrial production, and exploding as a phenomenon following ‘liberalisation’ of bank lending controls three years previously. Now, with 90% of bank lending going to the financial and property sectors, significantly worse, we wonder why the UK has a productivity gap compared to other advanced nations. The causes are deep, and their history is long.

The repeal of the nationalisation of development values in the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act demonstrates the power of law over economics, and the sustainability and vitality of our cities. It is a nation’s nuclear option. By embracing so-called free market values, a nation exposes itself to forces that are greater than even its government – namely the international financial sector.

They have broken governments before, in dramatic fashion, and, through land and property, we can see them once again breaking society, but in slow but steady motion.

While Brexit promised Britons that they would “take back control”, it clearly did the opposite – diminishing the collective weight of the European Union’s legislative oversight, and exposing the UK even further to the whims of international financiers.

Always the plan of Brexit ! pic.twitter.com/nmd2is9bmY

— Safetyadviser (@WeeDogWalker) August 6, 2023

We can therefore expect further social debasement and speculative bubbles in property, as observed by McEwan half a century ago, to accelerate even further.

It is an extraordinary challenge to the imagination to envisage where this leads. Or perhaps it isn’t. The same financiers, enormous financial institutions, are now investing heavily in homes for rental. Even retailer John Lewis is getting in on the act. They simply do not expect us to be able to own property in the future, nor are they fearful of competition from the government (social renting) in this regard.

We also have so-called ‘Freeports’, which are, in fact, vast tracts of land, inland, with relaxed financial and, naturally, planning legislation. Expect these multiple square kilometre zones to lay down markers for the rest of the country, attracting investors, and therefore jobs and interest, but in an environment with even less social value. Expect a two-tier Britain as the first stage of this process, with a second stage in which it may become ‘inevitable’ that the rest of the country follows the Freeport lead.

This is the true promise of Brexit.

Expect a two-tier Britain as the first stage of this process, with a second stage in which it may become ‘inevitable’ that the rest of the country follows the Freeport lead. This is the true promise of Brexit.

Thinking of the environment

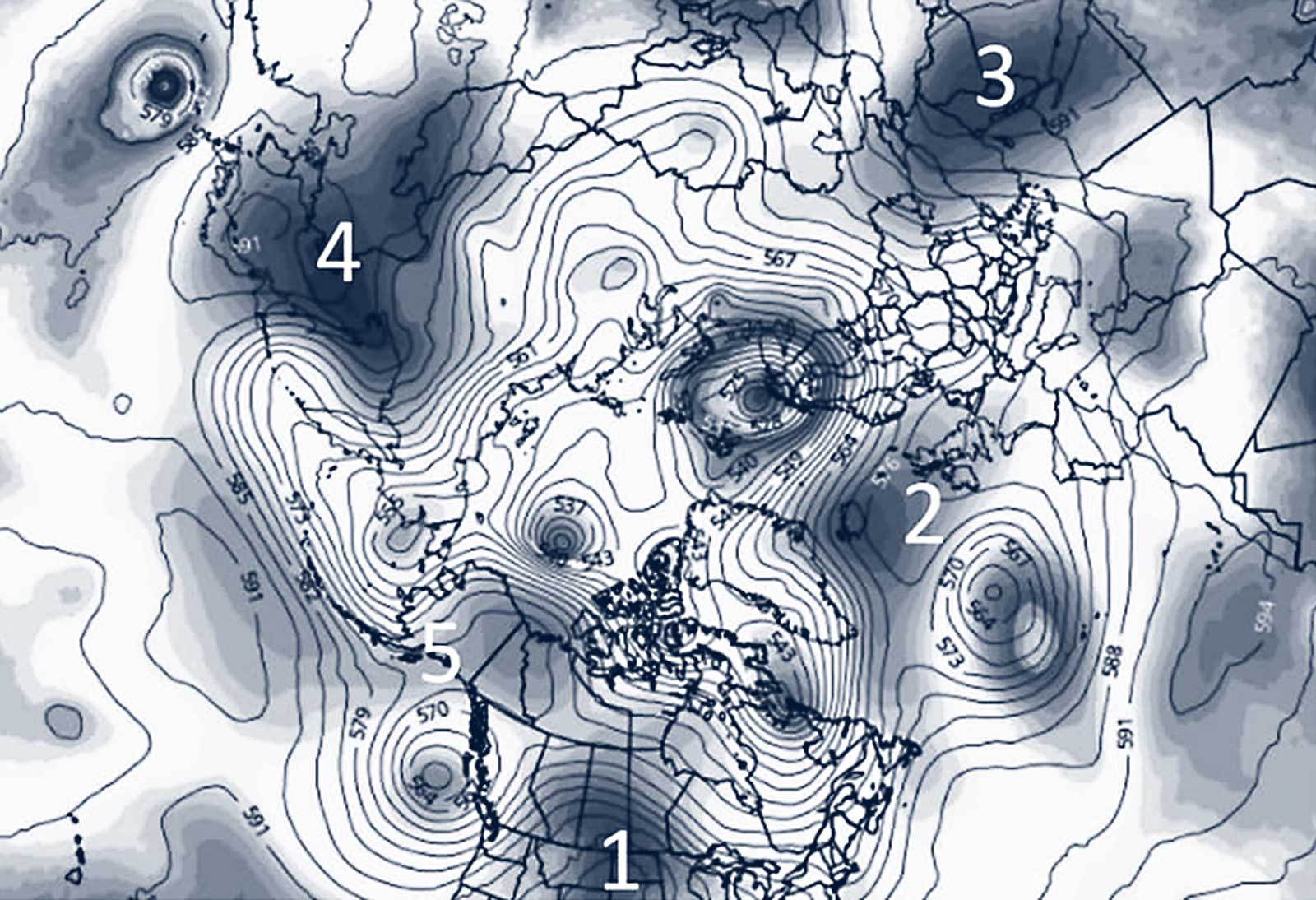

Interesting things happen when oil prices are high. McEwan’s suggestion of mandatory Environmental Impact Statements for projects of a certain size is enlightened, not just because it calls for such things as an objectively measurable energy balance sheet, but also because such statements would include social and financial factors. He goes on to suggest that they could be used as a vehicle for aligning architects’ interests inherently with those of the public, by compelling architects to uphold the values of such statements, and likewise refuse commissions where statements by a previous architect may have fallen short. It would likely be a very unpopular administrative overhead in this day and age of bloated and inefficient bureaucracy, but the concept itself is sound. Critically also, it would “drag into the open the financial basis of development”, a key source of controversy in planning matters today.

Financial viability assessments are a problem nation-wide. Developers are constantly wriggling out of their obligations to provide the required number of affordable homes. Councils need more support from @mhclg to get to grips with this issue and to help solve our housing crisis https://t.co/xrvHtvudNU

— Michelle Lowe (@MichelleLowe14) April 27, 2019

Four tasks for architects

MacEwen, in his “passionate constructive criticism by one who is not an architect but loves architecture”, gives us, the profession, four tasks to take away, as relevant now as they were then. Their headlines are worth quoting in full:

- The first task is to reduce the consumption of energy and other scarce resources

2. The second task for Architects is to ensure, so far as it lies within their power, that their skills and the nation’s schools resources applied to the satisfaction of the essential needs of the community

3. The third task for architects is to promote forms of professional practice that will release the skills, creativity, enthusiasm, and sense of commitment that many architects possess but cannot use in any satisfying way

4. The fourth task for architects emerges clearly from the other three. It is to rethink the role, functions, and structure of the professional institute.

Perhaps the practice of architecture demands an even more radical reassessment, but we could do worse than take this advice to heart, rather than let it languish for another half century.

Author: Malcolm MacEwen

Year of Publication: 1974

Enjoy the read? Now watch the films.

The future of architecture is not what you think

Follow to find out what it might look like.